Noiʻina

'Iolani Palace 1893 Abu Bakar African-Americans ali'i architecture Austronesian Austronesian languages Black Blacks colonialism Culture Hale Naua Hawaii Hawaiian Hawaiian culture Hawaiian history Hawaiian language Hawaiian religion Hawaiian spirituality Hawaiian veterans History Japan Kalakaua Kamehameha Kamehameha I language Liliuokalani Lua Malaysia Oahu Pele Philippines princess kaiulani Protest Republic of Hawai'i royalty soldiers speech Tagalog Territory of Hawaii volcano voyaging canoe wahine women

Bray and Reincarnation

Reposting an article on the topic

The Kahuna and Reincarnation

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Thursday, June 11, 1959 – Clarice B. Taylor’s “Tales about Hawaii“

“Did the Hawaiian believe in reincarnation?” asks the haole “seeker of the truth” of Daddy (David K.) Bray in trying to find the secret of the power of the Kahuna.

“Yes and no,” Daddy Bray replies. “The Hawaiian did not call it reincarnation, but his beliefs were very similar to what you call reincarnation.”

First of all, Daddy Bray explains, the Hawaiian did not believe in death. He believed that life went on eternally and never died.

When the Hawaiian left this life, his soul either went straight to heaven or it was sometimes lost and consigned to hell. But hell to the Hawaiian was an underground cavern where the soul lived a monotonous life. There were no hell fires.

COULD VISIT EARTH

The soul in heaven could visit earth at will – it could go into hell and rescue a lost soul.

Sometimes heavenly souls were reborn on earth into the same family. Then you have a real reincarnation.

Sometimes heavenly souls returned to take possession of a body or person.

But the aumakua was the real “reincarnation” as the Hawaiian saw it.

If a man was good and prospered – it was because he had a “powerful aumakua,” ancestor who visited him and directed his actions. The Hawaiian of today call his aumakus his “inspiration” because not other word explains the situation.

If am man were bad and suffered for his sins, then his aumakua was said to have deserted him. At death, his soul wandered and became lost because his aumakua had deserted him and did not look after his soul.

ONE OR MORE

Each person has an aumakua and a spiritual person has more than one. A commoner might have a mother or grandmother as his aumakua.

An alii (nobleman) coud claim any one of the gods in heaven as his aumakua as well as some ancestor. The more aumakua the better. But, an aumakua, like a god, must be treated with care. Regular prayers and offerings must be made by the living person.

Sherwood Forest: Seeing Beyond The Trees

(Originally published in: https://www.civilbeat.org/2019/07/sherwood-forest-seeing-beyond-the-trees/)

To many in Waimanalo, the forested area in the nearby beach park known by local residents as Sherwood Forest is more than a landscape. It is an area that holds the memories of morning walks, dates, family outings, birthdays and weddings.

When the mayor of Honolulu announced plans to build a multimillion dollar sports centers, local residents went up in arms. Many local residents argued that the sports center was the first step towards gentrifying “Nalo Country.”

Others argued that there were undocumented bones near the area and it is one of the “first contact landing sites” for ancient Polynesians on Oahu and therefore the area should not be developed.

Others still argued that no one in the community really knew about the community meetings about the sports center therefore they were not informed.

Waimanalo Sherwood Forest demonstrators along Kalanianaole Highway, May 3.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

Whatever the argument, it is clear that there is an underlining difference in values between local residents and the pro-developer City Council — kaiaulu, or community.

Over the last few years we have seen condos rising up in Kakaako and subdivisions in Kapolei, but these are not real communities. Local people can not afford to live in Kakaako’s luxury condos, hence why Kakaako is a ghost town at nights. Kapolei and Wahiawa are popular for military families but as soon as their tour of duty is over, they leave.

These are not real communities in the sense that Waimanalo has been and fights to be. People know each other’s problems. People know who is pregnant and who just got a new job. They care for each other and despite issues, they remain a close-knit community.

Throwing money at a place does not turn it into a living community. That’s one of the many issues with gentrification — it is developed for a particular affluent segment of the population and geared towards trends rather than sustainability and meaningful human connection.

An Issue Of Culture

Sherwood in many ways represents that clash between competing ideas of community “development” that is going on throughout Hawaii nei.

Should development only favor a small portion of the population? What happens to the core ideas of kaiāulu and aloha when you impose development from an unwilling community?

Who benefits from state and county development schemes? Not in dollar terms but in tangible benefits for residents who physically live in that community 365 days a year?

There is also an issue of culture.

Native Hawaiians are a communal culture with a set of underlining meheuheu (customs) which put into practice values and traditions. Meheuheu then had helped turn groups of families into ahupuaa-based communities and later as part of a national community. While people often complain that Native Hawaiians are anti-development, that is not true.

“We should support communities that want to remain intact as real living communities.”

Native Hawaiians had huge taro paddies and changed the landscape but when they did, it should benefit everyone in the community because that was part of the meheuheu. But is it precisely because of meheuheu that Hawaii was able to establish a fully functioning culturally pluralistic society beginning in the Hawaiian Kingdom era.

When people think in terms of community and meheuheu, it benefits not just Kanaka Maoli but all residents because it makes Hawaii livable and uniquely beautiful.

We should support communities that want to remain intact as real living communities. Nothing less would be to denying the time honored meheuheu of people in those areas.

Sherwood is not just about trees. It’s about the community.

Respiratory Therapists Are Among Our Unsung Heroes

(Originally published in: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/04/respiratory-therapists-are-among-our-unsung-heroes/)

All of our front-liners deserve our praise, aloha and respect for all that they do. These include our blue collar workers (our cashiers, janitors, security guards, delivery drivers, etc.) and gold collar workers (our medics, hospital staff, nurses, and doctors). They are the wai that feeds the loi.

One of the least talked about front liners in the medical field has been our respiratory therapists.

COVID-19 is a respiratory virus and these people are the last line of defense. They, along with doctors and nurses, play a pivotal role in this crisis and yet are normally lumped in with nurses despite their specialization.

In Hawaii, most RTs are locally born, bred and trained. Many of them got into that profession because of an experience with a loved one who had a respiratory illness. They know firsthand both as medical professionals and from the patient’s side.

Since they are from our community, they also have a special aloha with our community and most opt to stay in Hawaii despite better pay in the U.S. mainland.

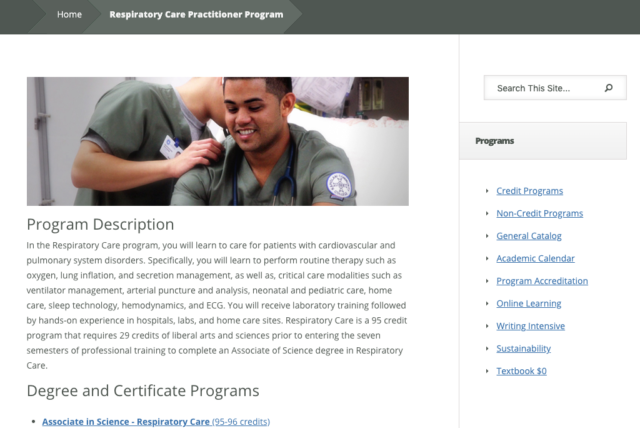

Normally, RTs study at an Associate of Arts program at Kapiolani Community College and then take a board exam upon completing an AA. Class sizes (less than 22 are admitted into the program) are kept small in order to give more individualized attention.

A hospital corpsman calibrates a ventilator aboard the USNS Comfort as the ship prepares to admit patients in support of the nation’s COVID-19 response efforts in New York on March 31.

Flickr: Navy Medicine

Depending on your scoring, you become a Certified RT (CRT) or a Registered RT (RRT). But RTs begin their hospital or clinical training from the very first semester.

Upon being certified or registered, one can go into a hospital case, out-patient case, or to home care, such as setting up CPAPs (continuous positive airway pressure) and oxygen tasks including nursing homes. RTs handle everything from helping premature babies with their breathing to testing for asthma, to putting car accident victims on a ventilator to assisting those on life support.

When someone is pulled off of life support, they are pulled off by an RT. Literally, RTs are there from babies to kupuna. As Kalena Frank, a RRT, explains, “RTs are there for the first breath and the last breath.”

With the COVID-19 outbreak, the role of RTs has been more critical. RTs are the ones who set people up on ventilators. Even if there was an abundant supply of ventilators, you still need RTs to manage them. According to Kalena Frank, Hawaii hospitals had been preparing for worst case scenarios of COVID-19 similar to New York for the last month.

A screen shot from KCC’s website on its Respiratory Care program.

While only 13% of COVID-19 cases require ventilators, any sharp increase like in New York would not only put a strain on ventilators but on the RT staff capacity. While there are about 500 ventilators in storage, there are only around 230 RTs statewide.

While 230 may sound sufficient, anyone who is put on a ventilator due to COVID-19 requires 24-hour management — on top of the 24-hour management of non-COVID-19 cases they were handling prior to the outbreak.

This means that any sharp increase in COVID-19 cases would also reduce the amount of attention someone else on life support or a premature baby receives and will be scaled back due to staffing issues — thus straining other critical medical services. Some RTs who have come into contact with COVID-19 patients have already been sleeping in their cars or in tents in order to avoid infecting loved ones and patients.

In light of all of this, we should be thankful for our medical teams, including RTs such as Kalena Frank and support them wherever we can, including not putting their lives in danger. After this crisis, hopefully more of our community will be inspired to take notice of the role our RTs play, and perhaps some may consider joining this honorable profession.

Shared Histories Between Filipinos And Hawaiians

(Originally published at: https://www.civilbeat.org/2019/08/filipino-experience-similar-to-that-of-kanaka-maoli/)

For many Filipinos born and raised in Hawaii, there is a sense of shame of being Filipino with such terms as “bukbok,” “pinoy,” and “Flip” existing. This is accentuated with the horrid ethnic jokes on the radio and the perception that Filipinos in Hawaii speak with accents.

But there is more to it than that. In the Philippines, skin whitening is a multi-million dollar industry. Being “kayumanggi” or brown-skinned is seen as not being as attractive as the mestizo or fairer skinned Filipinos.

This comes from the internalized colonization from over 400 years of Spanish and American rule. Unfortunately, some of internalized self-hate and sexism makes it into our local Filipino community to the point that some local Ilocanos resent being called Filipino.

But Filipinos have a proud heritage in the Philippines and in Hawaii — a heritage that often runs parallel to the experience of Kanaka Maoli. Like the shame felt by local Filipinos, there was a point too in Kanaka Maoli history where even the term “kanaka” was associated with being backwards (read: brown).

The bronze statue of Queen Liliuokalani on the makai side of the State Capitol. Native Hawaiians and Filipinos have an intertwined history.

While many Filipinos here might be acquainted with the Sakadas or sugar plantation worker history, many may not be aware of the deeper connections that existed prior to the arrival of the Sakadas. Filipinos may have been in Hawaii around the same time as the Japanese and Chinese merchants began to come to Hawaii during the reign of Kamehameha I due to the Spanish trade (particularly the Manila Galleon Trade).

During that time, the Spanish East Indies (now the Philippines and Micronesia), the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and Malaya were considered part of “Greater Polynesia.”

As “Greater Polynesia” became more integrated into colonial empires, “Greater Polynesia” became “Oceania.” But the fact that Greater Polynesia / Oceania was composed of related peoples and languages was not lost to Hawaiians like King Kalakaua, who created the “Star of Oceania” royal honor.

In the 20th century, however, with the effects of colonization and the Cold War, Oceania became a bordered region and this shared sense of Oceania / Austronesian / Pasifika / Pacific Islander identity was largely suppressed until the revival of navigation under such people as Mau Piailug. With that suppression, the pre-Sakada interaction between the mutual nationalism and shared experiences of Filipinos and Native Hawaiians was largely forgotten.

Naturalized Subjects

We know from naturalization records, there were Filipinos who naturalized as Hawaiian subjects in the 1850s and there were Filipinos in the Royal Hawaiian Band. One member in particular was Jose Sabas Libornio. Libornio is a forgotten hero.

When Queen Liliuokalani was deposed, members of the Royal Hawaiian Band were forced to take an oath to the new government. But most refused and Jose Libornio became leader of the new Hawaiian National Band, who then went around the U.S. and Europe promoting Hawaiian independence and popularizing Hawaiian music.

The refusal of Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians like Jose Libornio inspired Ellen Prendergast to compose a mele for a hula called “Mele ‘Ai Pōhaku.” In fact, Jose Libornio was one of the two people specifically mentioned by Ellen Prendergast to write a mele for them because he was “loyal to Liliu.”

In turn, Jose Libornio turned the lyrics into a musical composition and thus the song, “Kaulana Nā Pua” was born. Libornio was at one point arrested for his loyalty and eventually moved to Peru due to the heartache he felt at having both of his countries — the Philippines and Hawaii — absorbed into the United States. But in his photos in Peru, he still proudly wore the medals he was given by the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On the other side of the ocean at the same time period, Filipino nationalists such as Apolinario Mabini saw people such as King Kalakaua as a forerunner of a Pan-Malay movement and the Hawaiian Kingdom as proof that a progressive democracy could exist under a native Pacific Islander regime. In essence, Hawaii’s very existence was a threat to the propaganda that Spanish authorities insisted that the so-called indios or native Filipinos were incapable of self-rule.

People such as Libornio would have been aware of the events concurrently happening in the Philippines which while Hawaii was suffering under Republic of Hawaii, the Philippines launched the first successful anti-colonial revolution in Asia — and many in Hawaii was supportive of that. But as events unfolded, 1898 became not only a painful year for Native Hawaiians but also for Filipinos as both peoples lost their hard won independence to the United States within three months of each other.

Two Fledging Democracies

The fact that the United States had taken over two fledging democracies that shared ancestral links and was part of Oceania was not lost on Native Hawaiians. Robert Wilcox for example was in touch with the Philippine Independence Missions to the United States and wrote to General Antonio Luna in 1899 and again in 1900 that “I have already made up my mind to join with you and your country against America in the case they insist to ignore the right [of independence], the justice of your cause…”

Wilcox even had given though of raising a Hawaiian volunteer battalion to go to the Philippines to support Filipinos in their quest for recognition of their independence from Spain and the United States.

It was also an open secret at the time that Princess Kaiulani had supported Filipino and Cuban nationalists, hence a reason for her involvement in the Red Cross. Filipinos have been allies of Kanaka Maoli and Kanaka Maoli had been allies of Filipinos especially in the 19th century.

Filipinos in Hawaii have enriched our island’s history and likewise, there has been Hawaiians who had supported Filipinos in their quest for national liberation and democracy. Filipinos have also been at the forefront of activism and in the labor movement here (think Pablo Manlapit) and many Hawaiians — myself included — have Filipino blood. Even outside of activism and within establishment circles, there has been successful Filipinos in politics, in healthcare, in education and in the military.

“We are Mauna Kea” is more than a slogan.

Filipinos should not be ashamed of who they are and should be proud that they do have a rich history in Hawaii and people such as Libornio were aloha aina like their Kanaka Maoli cousins. Likewise, Kanaka Maoli should be proud of Kanaka Maoli leaders such as Robert Wilcox who understood the need for solidarity.

If anything, the recent actions on Mauna Kea have affirmed this history and it is fitting that a Filipino flag flies near the kupuna tent, as the Filipino flag was once banned by American colonial authorities and it serves to remind all of us in order to heal, we need to understand that we are who we once were.

While opponents may argue that that the TMT is needed for humanity, the Mauna has shown itself that it is humanity itself bringing back the peoples of the canoe from the Philippines to Micronesia to Fiji to Tonga and to all the indigenous peoples throughout the world.

“We are Mauna Kea” is more than a slogan. It is re-imagining Hawaii not as merely the “Aloha State,” but as the “Aloha Nation.”

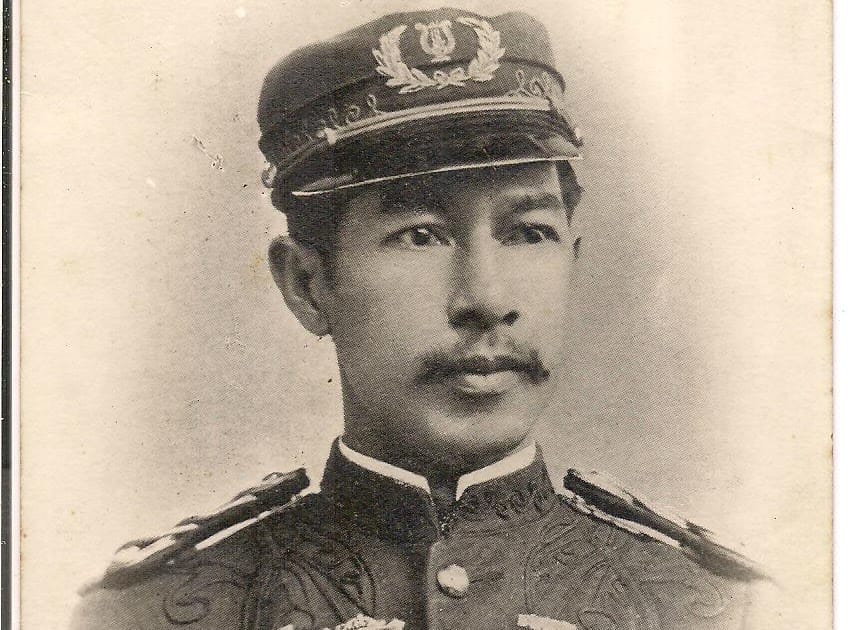

Jose Libornio, Filipino Bandmaster of the Hawaiian National Band

Few may remember him now especially in the Hawaiian and Filipino communities but in his time, he was one of the most respected people in the Hawaiian Islands.

Maestro Jose Sabas Libornio Ibarra was born in Santa Ana, Manila at the time that colonized by Spain. He originally was supposed to be part of the Manila Symphony Orchestra but due to the racism by the white Spaniards of that time, he left for Hawaiʻi.

Eventually he found himself in Hawai’i where he became part of the Royal Hawaiian Band and worked directly under Maestro Henry Berger. He was decorated by both King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani.

In February of 1893, he and other Royal Hawaiian Band members refused to take the oath to the Provisional Government. The ones who refused, formed a new bang, the Hawaiian National Band or Bana Lahui Hawaii. He became its bandmaster and he and the band continued to refuse to take the oath of allegiance to the Provisional and later Republic of Hawai’i. Supposedly Henry Berger discouraged this and told them that they would be eating stones.

The refusal of him and others to take the oath became the inspiration for the lyrics of the mele, “Mele ‘Ai Pohaku”, by Eleanor Kekoaohiwaikalani Wright Prendergast. Prendergast was a friend of Libornio and Liborio and two other Hawaiians talked about their financial predicament to her while still asserting that they will “never take the oath to the haoles”. It is believed that she composed it as a chant or may have used a melody from another song. But Libornio was so moved he created an entirely new melody.

That song became “He Inoa No Ka Keiki O Ka Bana Lahui: He Lei No Ka Lahui Hawaii” as the name implies, a song for the band. The band then traveled to the US where the song became popular especially among the Hawaiians in the diaspora. Around the time of the 1895 Uprising against the Republic, the song title changed to “Kaulana Na Pua”.

But in Hawaiʻi, which was a separate country with its own copyright laws, Libornio maintained Prendergast because the lyrics were her own. She was the haku mele after all. Libornio wrote other nationalist songs including a march for Queen Liliʻuokalani.

In the aftermath of the Uprising, the Republic of Hawaiʻi began to strip citizenship from naturalized citizens as well as deporting non-citizens who were found to have “royalist sympathies”. As a result of his band activities and his status as a non-citizen, he was a target for deportation by the Republic. Libornio moved to Peru but continued to wear the Hawaiian Kingdom medals, which can be seen in his official photo. Before leaving for Peru, fearing that Americans might copyright the song due to its popularity, Libornio submitted it to the US Library of Congress in 1895 as the “Aloha Aina” song.

Libornio continued to have a profound musical career in Peru and the “The Marcha de Banderas”, a composition he wrote, is still played during the raising of the Peruvian flag and considered the second national anthem of Peru. In many ways, “Kaulana Nā Pua” has also become a secondary national anthem for Hawaiʻi.

The Emancipation Proclamation in Hawaiian

When the Emancipation Proclamation reached Hawai’i, it was widely published. This is a copy of it in Hawaiian. Although slavery had long before been abolished, Hawaiians saw this a great achievement for the advancement of human rights. Several papers published it in Hawaiian or in English. This one is from Kuokoa 1/31/1863.

The Story of John Blossom, a Black Man At the Court of Kalākaua

One of the figures of Black history in Hawai’i that I had done research on was Ioane Mōhala. I had to rely heavily on newspapers and oral histories for this. Ioane Mōhala was the Hawaiian name for John Blossom.

John Blossom was born in Jamaica and was the son of British plantation owner and an African slave. He was initially a slave and became freed in 1833 as Britain abolished slavery. Upon that time he joined the crew of a merchant ship and was enslaved in the US before escaping and ending up in Hawaiʻi in 1850.

John Blossom ended up meeting Caesar Kapaʻakea where he was his valet. Kapaʻakea already was married and had a family with Analea Keohokālole. Eventually Blossom became the estate manager for Keohokālole.

Two of the children would become monarchs–David and Lydia. Blossom was well liked by Kamehameha III and was welcomed at court. This was in sharp contrast to the US and Europe. He also was given an honorary commission in the Hawaiian army.

His relationship with the Kapaʻakea family was such that he ate with the family as equals and was called an uncle. Blossom would go back to Jamaica and married a Black woman by the name Marea. They moved back to Hawaiʻi and had several children. One of the children would be the godchild of David Kalākaua and would work in the household of William Lunalilo and later the Crowningburg family. A daughter worked in the household of Queen Emma.

In 1886, a protracted campaign to oust Kalākaua was started. Among the things spread was that Kalākaua was the son of John Blossom because Black and royalty could not inhabit the same body. When Queen Lili’uokalani began to question American hegemony, that rumor was recirculate by the Calvinist missionary newspaper, The Friend.

There was no truth that these rumors as all of Kapa’akea’s children were born after John Blossom’s arrival. But because of prejudices at the time, this was used to demonstrate how unfit Kalākaua and Lili’uokalani were to rule. Nevermind how educated and accomplished the two monarchs were, any ounce of Black blood was cause to get rid of them.

Looking At A Post-COVID-19 Pono Economy

(Original: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/05/looking-at-a-post-covid-19-pono-economy/)

The economic anxiety has been profound during this time of crisis. Understandably, many people want things to go back to “normal.”

The governor’s own economic recovery plan as of now is to essentially rebuild the tourism industry and go from there. The governor’s own task force is composed mostly of corporate talking heads and some from academe. It did not represent a broader range of the community and basically underlined the message that we have to return to “normal.”

That’s is exactly where the problem lies. What we had prior to March was always not sustainable, particularly for the working class, women, and for Native Hawaiians. We had gotten so used to colonial clichés like “aloha spirit,” “Lucky you live Hawaii” and “the paradise tax” that too many accepted that “it is what it is.”

To be clear, what was left behind in March in terms of the economy and its social impact was one where:

- unemployment was low due to, among other reasons, the fact that people were working two or more jobs and the state was not keeping track of underemployment;

- the houseless population was among the highest in the U.S.;

- luxury condos were being built faster than public housing;

- a prison system so full that we were exporting inmates;

- over-tourism that wrecked the quality of life for local residents and caused serious environmental decay;

- a substantial brain drain of skilled people leaving due to the high cost of living;

- related to the above, a disproportionate number of people in their early 30s to 50s leaving Hawaii — a key age group as that is the age group that normally has finished school, has begun a stable career and puts in the most income tax revenue;

- Native Hawaiian issues, including Mauna Kea but also the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, largely being ignored or brushed aside in favor of settler development;

- a state-wide IT infrastructure built in 1983 (as many in the unemployment insurance system have found out);

- a state bureaucracy that had become so rigid and outdated that it could not be mobilized to help out other departments (again as many in the unemployment system have found out);

- reported domestic violence against women being higher than the national average; and

- reported suicide rates among Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders and LGBTQ youth, being significantly higher than the U.S. average.

Recently, however, due to the pandemic, more kipuka (tracts of land surrounded by recent lava flows) of life have merged.

Thirty Meter Telescope demonstrators moved a Hawaiian flag atop the Kipuka Puu Huluhulu Native Tree Sanctuary and Nature Trail above the Maunakea Access road in July 2019.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

For the first time in years, local people were able to enjoy our own beaches, including Waikiki Beach, without having to compete with the swarms of tourists. Kids were able to play on the streets due to there being less traffic. Parents were learning Hawaiian in order to help their kids with their homework. People have now understood how awful and inhumane is the IT structure within the state.

People were shopping and giving food to kupuna. People were reconnecting with the aina, and the aina was regaining its splendor. Conversely, we saw more clearly the people in our neighborhoods who showed no concern for others, did not understand how rights during an epidemic was long ago decided in cases like Jacobson vs. Massachusetts, and who felt that their haircuts were more important than the lives of our kupuna.

Address Our Inequalities

What we need now is to transform the society. We have already seen some thinking along those lines in the “Building Bridges” feminist economic recovery plan from the Commission on the Status of Women. The plan outlines shifting Hawaii away from tourism and the U.S. military and focusing on green technology, more access for women and Native Hawaiians to capital to build up their own businesses, midwifery, and other initiatives.

It is a great start and shows us what can be done within the state bureaucracy when forward minded women are given space to think and speak.

We need to address our inequalities but also need a new way to look at our economy itself in terms of decolonization and sustainability. Rather than looking at stock markets, development and gross domestic products, we need to develop an economic measurement similarly to Bhutan’s gross national happiness — maybe a Gross Domestic Pono indicator.

With a “GDPo” we then can factor in quality of life for local residents, social justice, cost of living, stable career growth, aloha aina values, impact on Native Hawaiian culture, indigenous economic values, impact on women, the brain drain factor and sustainability.

Using that as a standard, we then can have a better idea if a proposed plan, project or economic activity would add to or remove pono from our community and we can also bring the GDPo down to a neighborhood level in order to assess how neighborhoods are fairing.

In looking at a pono economy and how decolonizing it could play out, I am also reminded of the richness of centuries of Native Hawaiian thought on wealth, resource management and economic planning. Rich people were those who had the most to share in a community. Wealth was not to be hoarded but shared.

Take, for example, the way Hamakua judged things on the micro-economic level: production was seen as not just the individual taro fields and fisheries but what could be cooked in the imu (underground oven) to be eaten by the entire community because a community cannot simply eat taro alone. Imu-nomics, if you will.

What we need now is to transform the society.

The question then comes to mind will we leave for the future an imu of rotten bananas because we have gotten used to it even though we know it’s unhealthy?

Or will we leave behind an imu of great varieties and tastes even if we may not enjoy it but for the next generation?

We need to build a better foundation for them, even if it is taking small steps like admitting we have an abusive relationship with over-tourism that we need to move beyond.

Plans such as the one put forward by the Commission on the Status of Women need to be considered seriously as well as redefining what constitutes economic output and deciding what type of imu we will be preparing. What we do in the coming months will help to determine what type of Hawaii will come into being.

Let us hope we will have the courage to demand a more pono society and that pono may be the new “normal.”

Community Voices aims to encourage broad discuss

Where the "First Hawaiian" Was Born

I was asked a question about where the “first Hawaiian” was born according to the Papahānaumoku, Wākea and Hoʻohōkūlani epic.

The answer is:

At a place called Moʻo-kapu-o-Hāloa which is the main ridge of Kāne-hoa-lani at Kua-loa, Oʻahu. This can be looked up in Abraham Fornander, Martha Beckwith and even in “Place Names of Hawaiʻi” by the eminent Mary Kawena Pukui.

Moʻo can mean lizard or supernatural dragon or in succession. Kapu means sacred.

The moʻo has long been one of the ancient guardians of Kama-lala-walu line of chiefs. Papahānaumoku, the earth mother, was of that line and thus all chiefs all derive from that line through her and her daughter, Hoʻohōkūlani. It is interesting to note the ties between royalty, lizards (moʻo or nagas), and dragons is something that is not just found among Hawaiians but among the our cousins throughout SE Asia and the Pacific but as well as throughout East Asia. There are also stories about kupua moʻo, dragon or lizard women, who would act as midwives to chiefly babies. It is said that one such powerful moʻo wahine was a midwife to Hoʻohōkūlani when she gave birth to Hāloanaka (which was the son that became the kalo plant) and Hāloa (which became the ancestor of the Hawaiian people).

Moʻo can also mean in succession. Moʻo aliʻi means succession of chiefs. Moʻolelo means a succession of stories. Moʻo kapu could therefore mean in succession of sacredness. Sacred lizard or the succession of sacred ones would all therefore make sense as a translation.

Therefore, next time one goes to Kualoa and sees that high Ridge, one can nod in acknowledgement that is where the “first Hawaiian” was born. That is where Wākea lived with Hoʻohōkūlani at one time. That is where the lines of chiefs and of the lehulehu had sprung down to the earth.

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.